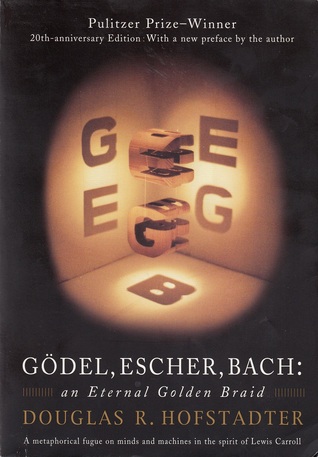

Contracrostipunctus by Douglas Hofstadter (from Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid)

note: if you like this dialogue, go buy the book! This transcription lacks the typography in the book that reveals exquisite hidden meanings and structure. Nevertheless, you'll notice still plenty of different levels of meaning in this entertaining story about records invented to break record players!

Achilles has come to visit his friend and jogging

companion, the Tortoise, at his home

Achilles: Heavens, you certainly have an admirable boomerang collection

Tortoise: Oh, pshaw. No better than that of any other Tortoise. And now would you like

to step into the parlor?

Achilles: Fine. (Walks to the corner of the room.) I see you also have a large collection of

records. What sort of music do you enjoy?

Tortoise: Sebastian Bach isn't so bad, in my opinion. But these days, I must say, I am

developing more and more of an interest in a rather specialized sort of music.

Achilles: Tell me, what kind of music is that?

Tortoise: A type of music which you are most unlikely to have heard of. I call it "music to

break phonographs by".

Achilles: Did you say "to break phonographs by"? That is a curious concept. I can just

see you, sledgehammer in hand, whacking on phonograph after another to pieces,

to the strains of Beethoven's heroic masterpiece Wellington's Victory.

Tortoise: That's not quite what this music is about. However, you might find its true

nature just as intriguing. Perhaps I should give you a brief description of it?

Achilles: Exactly what I was thinking.

Tortoise: Relatively few people are acquainted with it. It all began when my friend the

Crab-have you met him, by the way?-paid me a visit.

Achilles: ' twould be a pleasure to make his acquaintance, I'm sure. Though I've heard so

much about him, I've never met him

Tortoise: Sooner or later I'll get the two of you together. You'd hit it off splendidly.

Perhaps we could meet at random in the park one day ...

Achilles: Capital suggestion! I'll be looking forward to it. But you were going to tell me

about your weird "music to smash phonographs by", weren't you?

Tortoise: Oh, yes. Well, you see, the Crab came over to visit one day. You must

understand that he's always had a weakness for fancy gadgets, and at that time he

was quite an aficionado for, of al things, record players. He had just bought his

first record player, and being somewhat gullible, believed every word the

salesman had told him about it-in particular, that it was capable of reproducing

any and all sounds. In short, he was convinced that it was a Perfect phonograph.

Achilles: Naturally, I suppose you disagreed.

Tortoise: True, but he would hear nothing of my arguments. He staunchly maintained that

any sound whatever was reproducible on his machine. Since I couldn't convince

him of the contrary, I left it at that. But not long after that, I returned the visit,

taking with me a record of a song which I had myself composed. The song was

called "I Cannot Be Played on Record Player 1".

Achilles: Rather unusual. Was it a present for the Crab?

Tortoise: Absolutely. I suggested that we listen to it on his new phonograph, and he was

very glad to oblige me. So he put it on. But unfortunately, after only a few notes,

the record player began vibrating rather severely, and then with a loud "pop",

broke into a large number of fairly small pieces, scattered all about the room. The

record was utterly destroyed also, needless to say.

Achilles: Calamitous blow for the poor fellow, I'd say. What was the matter with his

record player?

Tortoise: Really, there was nothing the matter, nothing at all. It simply couldn't reproduce

the sounds on the record which I had brought him, because they were sounds that

would make it vibrate and break.

Achilles: Odd, isn't it? I mean, I thought it was a Perfect phonograph. That's what the

salesman had told him, after all.

Tortoise: Surely, Achilles, you don't believe everything that salesmen tell you! Are you

as naive as the Crab was?

Achilles: The Crab was naiver by far! I know that salesmen are notorious prevaricators. I

wasn't born yesterday!

Tortoise: In that case, maybe you can imagine that this particular salesman had somewhat

exaggerated the quality of the Crab's piece of equipment ... perhaps it was indeed

less than Perfect, and could not reproduce every possible sound.

Achilles: Perhaps that is an explanation. But there's no explanation for the amazing

coincidence that your record had those very sounds on it ...

Tortoise: Unless they got put there deliberately. You see, before returning the Crab's

visit, I went to the store where the Crab had bought his machine, and inquired as

to the make. Having ascertained that, I sent off to the manufacturers for a

description of its design. After receiving that by return mail, I analyzed the entire

construction of the phonograph and discovered a certain set of sounds which, if

they were produced anywhere in the vicinity, would set the device to shaking and

eventually to falling apart.

Achilles: Nasty fellow! You needn't spell out for me the last details: that you recorded

those sounds yourself, and offered the dastardly item as a gift ...

Tortoise: Clever devil! You jumped ahead of the story! But that wasn't the end of the

adventure, by any means, for the Crab did r believe that his record player was at

fault. He was quite stubborn. So he went out and bought a new record player, this

one even more expensive, and this time the salesman promised give him double his

money back in case the Crab found a song which it could not reproduce exactly.

So the Crab told me excitedly about his new model, and I promised to come over

and see it.

Achilles: Tell me if I'm wrong-I bet that before you did so, you once again wrote the

manufacturer, and composed and recorded a new song called "I Cannot Be Played

on Record Player 2", based on the construction of the new model.

Tortoise: Utterly brilliant deduction, Achilles. You've quite got the spirit.

Achilles: So what happened this time?

Tortoise: As you might expect, precisely the same thing. The phonograph fell into

innumerable pieces, and the record was shattered.

Achilles: Consequently, the Crab finally became convinced that there can

be no such thing as a Perfect record player.

Tortoise: Rather surprisingly, that's not quite what happened. He was sure that the next

model up would fill the bill, and having twice the money, he--

Achilles: Oho—I have an idea! He could have easily outwitted you, by obtaining a LOW fidelity

phonograph-one that was not capable of reproducing the sounds which

would destroy it. In that way, he would avoid your trick.

Tortoise: Surely, but that would defeat the-original purpose-namely, to have a

phonograph which could reproduce any sound whatsoever, even its own selfbreaking

sound, which is of course impossible.

Achilles: That's true. I see the dilemma now. If any record player—say

Record Player X—is sufficiently high-fidelity, then when it attempts to play the song "I

Cannot Be Played on Record Player X", it will create just those vibrations which

will cause it to break. .. So it fails to be Perfect. And yet, the only way to get around

that trickery, namely for Record Player X to be of lower fidelity, even more

directly ensures that it is not Perfect. It seems that every record player is

vulnerable to one or the other of these frailties, and hence all record players are

defective.

Tortoise: I don't see why you call them "defective". It is simply an inherent fact about

record players that they can't do all that you might wish them to be able to do. But

if there is a defect anywhere, it is not in THEM, but in your expectations of what

they should b able to do! And the Crab was just full of such unrealistic

expectations.

Achilles: Compassion for the Crab overwhelms me. High fidelity or low fidelity, he loses

either way.

Tortoise: And so, our little game went on like this for a few more rounds, and

eventually our friend tried to become very smart. He got wind of the principle

upon which I was basing my own records, and decided to try to outfox me. He

wrote to the phonograph makers, and described a device of his own invention,

which they built to specification. He called it "Record Player Omega". It was

considerably more sophisticated than an ordinary record player.

Achilles: Let me guess how: Did it have no moving parts. Or was it made of cotton? Or—

Tortoise: Let me tell you, instead. That will save some time. In the first place, Record

Player Omega incorporated a television camera whose purpose it was to scan any

record before playing it. This camera was hooked up to a small built-in computer,

which would determine exactly the nature of the sounds, by looking at the groovepatterns.

Achilles: Yes, so far so good. But what could Record Player Omega do with this

information?

Tortoise: By elaborate calculations, its little computer figured out what effects the sounds

would have upon its phonograph. If it deduced that the sounds were such that they

would cause the machine in its present configuration to break, then it did

something very clever. Old Omega contained a device which could disassemble

large parts of its phonograph subunit, and rebuild them in new ways, so that it

could, in effect, change its own structure. If the sounds were "dangerous", a new

configuration was chosen, one to which the sounds would pose no threat, and this

new configuration would then be built by the rebuilding subunit, under direction

of the little computer. Only after this rebuilding operation would Record Player

Omega attempt to play the record.

Achilles: Aha! That must have spelled the end of your tricks. I bet you were a little

disappointed.

Tortoise: Curious that you should think so ... I don't suppose that you know Godel's

Incompleteness Theorem backwards and forwards, do you?

Achilles: Know WHOSE Theorem backwards and forwards? I've never

heard of anything that sounds like that. I'm sure it's fascinating, but I'd rather hear more

about "music to break records by". It's an amusing little story. Actually, I guess I

can fill in the end. Obviously, there was no point in going on, and so you

sheepishly admitted defeat, and that was that. Isn't that exactly it?

Tortoise: What! It's almost midnight! I'm afraid it's my bedtime. I'd love to talk some

more, but really I am growing quite sleepy.

Achilles: As am 1. Well, I'll be on my way. (As he reaches the door, he suddenly stops,

and turns around.) Oh, how silly of me! I almost forgot. I brought you a little

present. Here. (Hands the Tortoise a small neatly wrapped package.)

Tortoise: Really, you shouldn't have! Why, thank you very much indeed think I'll open it

now. (Eagerly tears open the package, and inside discovers a glass goblet.) Oh, what

an exquisite goblet! Did you know that I am quite an aficionado for, of all things, glass

goblets?

Achilles: Didn't have the foggiest. What an agreeable coincidence!

Tortoise: Say, if you can keep a secret, I'll let you in on something: I'm trying to find a

Perfect goblet: one having no defects of a sort in its shape. Wouldn't it be

something if this goblet-let's call it "G"-were the one? Tell me, where did you come

across Goblet G?

Achilles: Sorry, but that's MY little secret. But you might like to know who its maker is.

Tortoise: Pray tell, who is it?

Achilles: Ever hear of the famous glassblower Johann Sebastian Bach? Well, he wasn't

exactly famous for glassblowing-but he dabbled at the art as a hobby, though

hardly a soul knows it-and this goblet is the last piece he blew.

Tortoise: Literally his last one? My gracious. If it truly was made by Bach its value is

inestimable. But how are you sure of its maker?

Achilles: Look at the inscription on the inside-do you see where the letters `B', `A', `C', `H'

have been etched?

Tortoise: Sure enough! What an extraordinary thing. (Gently sets Goblet G down on a

shelf.) By the way, did you know that each of the four letters in Bach's name is

the name of a musical note?

Achilles:' tisn't possible, is it? After all, musical notes only go from ‘A’ through `G'.

Tortoise: Just so; in most countries, that's the case. But in Germany, Bach’s own

homeland, the convention has always been similar, except that what we call `B',

they call `H', and what we call `B-flat', they call `B'. For instance, we talk about

Bach's "Mass in B Minor whereas they talk about his "H-moll Messe". Is that

clear?

Achilles: ... hmm ... I guess so. It's a little confusing: H is B, and B B-flat. I suppose

his name actually constitutes a melody, then.

Tortoise: Strange but true. In fact, he worked that melody subtly into one of his most

elaborate musical pieces-namely, the final Contrapunctus in his Art of the Fugue.

It was the last fugue Bach ever wrote. When I heard it for the first time, I had no

idea how it would end. Suddenly, without warning, it broke off. And then ... dead

silence. I realized immediately that was where Bach died. It is an indescribably

sad moment, and the effect it had on me was-shattering. In any case, B-A-C-H is

the last theme c that fugue. It is hidden inside the piece. Bach didn't point it out

explicitly, but if you know about it, you can find it without much trouble. Ah, me-there

are so many clever ways of hiding things in music .. .

Achilles: . . or in poems. Poets used to do very similar things, you know (though it's

rather out of style these days). For instance, Lewis Carroll often hid words and

names in the first letters (or characters) of the successive lines in poems he wrote.

Poems which conceal messages that way are called "acrostics".

Tortoise: Bach, too, occasionally wrote acrostics, which isn't surprising. After all,

counterpoint and acrostics, with their levels of hidden meaning, have quite a bit in

common. Most acrostics, however, have only one hidden level-but there is no

reason that one couldn't make a double-decker-an acrostic on top of an acrostic.

Or one could make a "contracrostic"-where the initial letters, taken in reverse

order, form a message. Heavens! There's no end to the possibilities inherent in the

form. Moreover, it's not limited to poets; anyone could write acrostics-even a

dialogician.

Achilles: A dial-a-logician? That's a new one on me.

Tortoise: Correction: I said "dialogician", by which I meant a writer of dialogues. Hmm

... something just occurred to me. In the unlikely event that a dialogician should

write a contrapuntal acrostic in homage to J. S. Bach, do you suppose it would be

more proper for him to acrostically embed his OWN name-or that of Bach? Oh,

well, why worry about such frivolous matters? Anybody who wanted to write

such a piece could make up his own mind. Now getting back to Bach's melodic

name, did you know that the melody B-A-C-H, if played upside down and

backwards, is exactly the same as the original?

Achilles: How can anything be played upside down? Backwards, I can see-you get H-C-A-

B-but upside down? You must be pulling my leg.

Tortoise: ' pon my word, you're quite a skeptic, aren't you? Well, I guess I'll have to give

you a demonstration. Let me just go and fetch my fiddle- (Walks into the next

room, and returns in a jiffy with an ancient-looking violin.) -and play it for you

forwards and backwards and every which way. Let's see, now ... (Places his copy

of the Art of the Fugue on his music stand and opens it to the last page.) ... here's

the last Contrapunctus, and here's the last theme ...

The Tortoise begins to play: B-A-C- - but as he bows the final H, suddenly,

without warning, a shattering sound rudely interrupts his performance. Both

he and Achilles spin around, just in time to catch a glimpse of myriad

fragments of glass tinkling to the floor from the shelf where Goblet G had

stood, only moments before. And then ... dead silence.