Great Composer Pilgrimage Part 3—Visiting JSB

What it’s like to sit in St. Thomas Kirche

I can’t believe it—I’m here!— sitting in a pew in St. Thomas Kirche. We arrived from the Leipzig train station just in time for the Sunday evening service. We’re singing a Lutheran chorale with the rest of the congregation. Behind us, we hear a heavenly boys choir from England singing Bach and Duruflé. (Visiting choirs and organists come daily to perform Bach here “at the source.”) They finish and the evening service continues. A woman sitting behind me has her eyes closed in bliss throughout the whole service. My friend Charla laughs at a joke the minister makes. I keep looking up and around in awe. This was the place! Here Bach spent much of his life writing and performing all the music that means so much to all of us—the St. Matthew Passion and those immortal cantatas. It’s easy to imagine him just right up there conducting the choir, or above on the side playing the organ.

The Bach statue outside St. Thomas Kirche

The renovated interior of St. Thomas Kirche

The church interior is completely renovated. Beautiful modern stained glass windows depict Bach and Mendelssohn! (Mendelssohn conducted the St. Matthew Passion here himself, and with that performance established the cult of Bach that continues to this day.) Oddly, the “newness” of the interior makes it easier to imagine how it felt to attend a service here during the 18th century. The church exudes a modern joy and even comfortable ordinariness. I can picture people coming to Sunday service to hear the cantor’s latest difficult modern music, and maybe even looking forward to his attempts to throw off the congregation with his outlandish organ harmonizations. Somehow, the renovated interior makes it easier to imagine ourselves at a Bach-led service instead of the ancient, grime-encrusted walls we usually experience in historic cathedrals and churches in Europe.

The stained glass window featuring JSB

The Mendelssohn stained glass window in St. Thomas Kirche, so appropriate for the composer who did the most to promote the music of Bach

What probably has not changed since Bach’s time are the acoustics, and they are superb—reverberant but with short enough resonance so that harmonic and chromatic changes sound full but not overly muddy. This clarity is evident as the service concludes with an organist playing a Bach toccata on the church’s new Baroque organ. Hearing this piece in this church on a beautiful Baroque organ so beautifully performed, I am incredibly moved.

The beautiful Baroque organ in the side loft

Martin Luther himself spoke here at this very church to establish Lutheranism two hundred years before Bach’s time. Yet St. Thomas Kirche is now essentially a shrine to J.S. Bach, As it should be.

“Hello there, Superintendent, I bring Bach.”

With only a metaphoric shovel in hand to “dig” up a cantata, I stand inside the church before Bach’s tomb. A plaque on a pillar relates a remarkable anecdote: in July 1949, Master Mason Malecki pushed a handcart with a casket of bones through the city of Leipzig, arrived at the church and said, “Hello there, Superintendent, I bring Bach.” Originally, Bach had been buried at the hospital cemetery at St John’s Church. But that church was destroyed during WWII and the Leipzig town council agreed to move his remains to St. Thomas, where they are today.

Bach's tomb in the central choir chapel of St. Thomas Kirche

There is more “Bach” in the side chapel. You can view some beautiful baptismal certificates for Bach’s children—eleven of his children were baptized in St. Thomas. I also saw a fascinating exhibit that detailed the history and process of one of his cantatas.

Baptismal certificate for Bach and Anna Magdalena's daughter Christiana Sibylla, who only survived one year

Plaque on the modern St. Thomas School building noting that this was also the site of the old Thomas School where Bach and his family lived from 1723 to his death in 1750.

The St. Thomas School is connected to the church. Bach and his family—with about 150 students— all lived in this building from 1723 till his death in 1750 (the original building is gone; it was rebuilt in 1902). Bach’s duties as cantor were to direct the choir rehearsals and performances in the four city churches, give instrument lessons, perform at funerals and weddings, contract instrumentalists, prepare text booklets for the cantata performances, supervise the school for one week once each month, hire out instruments and maintain them in good repair, and sell books and sheet music. Having had some personal experience with these kind of “catch-all” positions, I can imagine they were many other requirements Bach had to fulfill that weren’t directly stated!

Just across the street from the school was a beautiful home owned by Bach’s merchant friend, Georg Böse. His daughter Christiana Sibylla became a very close friend of Bach’s wife Anna Magdalena. Their house with its beautiful garden is now the home of the Bach Museum in Leipzig.

The room decor in the Arcona 14 (get it?) Bach hotel directly across the street from St. Thomas Kirche and next door to the Bach Museum—highly recommended! :)

You can’t help but notice that the longer you spend time studying classical music, the deeper emotional connection you develop to the music of J.S. Bach. To get a better context for Bach’s world and try to understand how such astonishing music came to be is a quest many of us share apparently. Musicians and music lovers from all over the world are drawn here for the same reason. Leipzig perceives this desire, and you can and should easily spend some days exploring just the exhibits at St. Thomas and especially the Bach museum across the street. I recommend this trip to everyone.

Bach Museum in Leipzig

I don’t think there can be a question that this is the most remarkable museum devoted to a composer in the world. It invites the visitor into recent Bach scholarship and discoveries while imparting a comprehensive overview of Bach’s life and activities. You see the famous Bach Hausmann portrait. A remarkable exhibit takes you through the detective work scholars employ to identify the manuscript of Bach, his copyists, and his students. You can view and hear a very recent Bach discovery (2005!) of an aria. Speaking of manuscripts—there are copies of them everywhere. You can view examples of the cantatas, the organ works, the B minor Mass, the Well Tempered Clavier, etc.—heaven!

A copy of Bach's Leipzig organ—however the organ bench was the actual one Bach used!

Another room exhibits a copy of the organ Bach played with the actual bench on which he sat. We learn Bach was perhaps most well known for his professional examinations of organs and see a document that includes the amount of wine and rum a church supplied him during an extensive examination! One room contains examples of Baroque instruments, including a beautiful double bass from St. Thomas that performed those cantatas during Bach’s tenure.

This double bass was one of the St. Thomas instruments during Bach's tenure. Bassists must have played it for Bach's cantata and Passion performances.

There is a model of the original St. Thomas school, as well as maps of buildings and grounds where Bach worked in Weimar and Anhält-Cöthen. An entire wall displays the extensive Bach family tree that Bach himself elaborated. But this wall diagram, unlike Bach’s drawing, includes dates of each person and buttons you can press to hear musical examples composed by the various family members. There is a listening room where you can listen to any piece of Bach’s you desire. Why ever leave?

Part of the wall exhibit of Bach's family tree with audio examples of music from many of the the family members!

Looks pretty serious! This spectrometric camera essentially decodes the "DNA" of Bach's manuscript.

Manuscript Detective Work

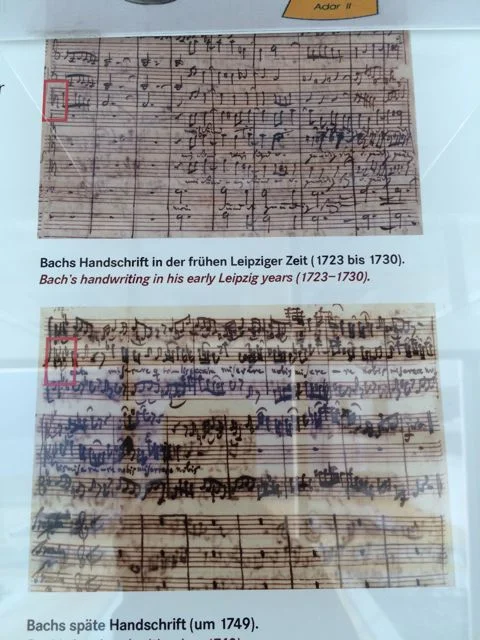

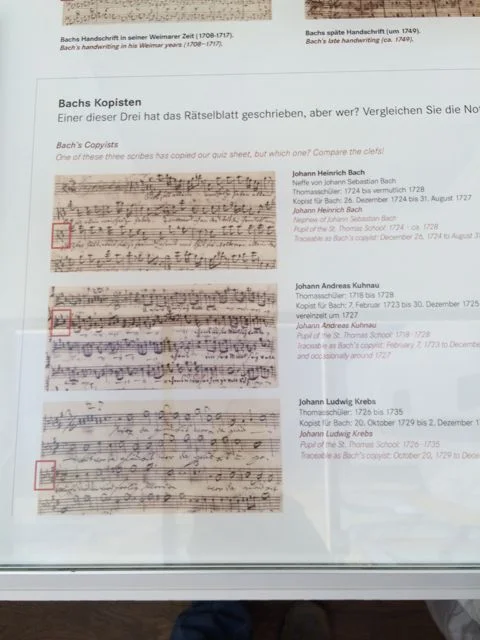

I joked about bringing a shovel to Leipzig to uncover a discarded Bach cantata. It turns out that Bach researchers have been hard at work with plenty ingenious shovels of their own. Front-center in the museum is an exhibit that details the current manuscript detective work of Bach scholars. They have identified three different stylistic periods in Bach’s manuscript, plus identified the manuscript of Bach’s wife Anna Magdelena, his children (W.F., C.P.E., etc.), and his copyists (often students like Johann Krebs and Johann Kuhnau).

Bach's manuscript in his pre-Leipzig years

Bach's manuscript in his early and late Leipzig years—the red boxes show the difference in the way he drew C clefs.

The manuscript styles some of Bach's student copyists in Leipzig— nephew Johann Heinrich Bach, Johann Kuhnau, and Johann Krebs.

Examples showing the difference between Bach's hurried everyday manuscript and his final careful style. Notice that when writing quickly, his note stems are on the right side of the head instead of the left. I notice this with other composers as well. I used to think this meant they were left-handed like me, but I guess that's not the case!

Another example of why the Bach Museum in Leipzig is in a class of its own. They show here the difference between Bach's gorgeous final copy of a piece...

...and the far rougher, though more exciting, original manuscript of the same piece.

Using a high-precision camera and spectrometric analysis of the ink, scholars are able to identify who wrote each note and mark in the music. There is a manuscript page showing counterpoint exercises shared by Bach and his son Wilhelm Friedemann.

An absolutely priceless document—a counterpoint lesson with Bach and his son Wilhelm Friedemann. Bach's writing is inside the red box. W.F.'s exercise is in invertible counterpoint (melodies that work equally well when the top and bottom voices flip). It's quite good. But his dad's examples take things up a notch with counterpoint at double and half the speed—such a show-off!

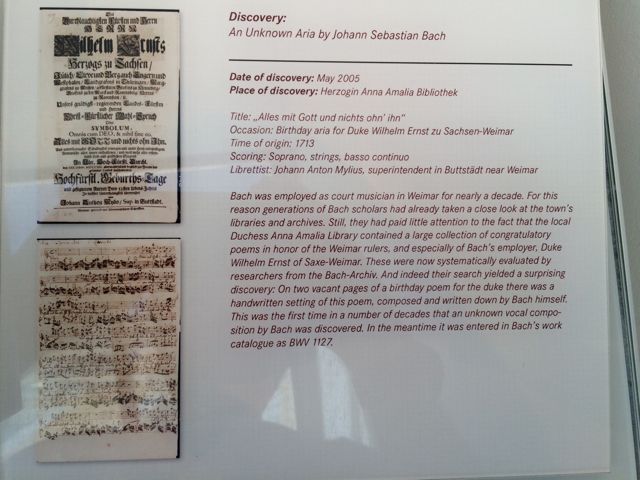

We see a page from the B minor Mass where his son Carl Philip Emanuel inserted some different notes and text. Armed with the algorithms of Bachs manuscript and handwriting, scholars have very recently ventured into the countryside and nearby towns to try and discover Bach documents—with success! We see a newly discovered aria Bach composed as a birthday present for the Duke of Saxe-Weimar researches discovered by combing through the library of a local duchess.

Recently discovered Bach aria lurking in the library of a Duchess in Weimar.

Researchers have also uncovered a receipt from one of Bach’s organ examinations that itemizes “supplies” furnished by the church parish to Bach: 22 pitchers of Moselle wine, brandy, beer, coffee, tea, sugar, tobacco, and pipes. Clearly, organ examination is a thirsty business.

Recently discovered receipt of expenses for Bach's examination of an organ at St. John's Church in Gera—includes 22 pitchers of Moselle wine, brandy, beer, coffee, tobacco, and pipes. All clearly necessary for proper organ examination :)

The Bach Chest—Quaerendo invenietis (“seek and you shall find”)

The museum has a May 11, 1747 copy of the Leipzig newspaper detailing Bach’s visit to Frederick the Great in Potsdam.

Leipzig newspaper comments on Bach's visit to King Frederick II at Potsdam.

This was the famous visit where the king presented Bach with a treacherously chromatic theme and challenged him to improvise fugues on the spot. Bach later sent the king far more than he bargained for—The Musical Offering, in which he quoted the Gospel of Matthew “seek and you shall find” as an exhortation for the king (and probably the king's Kapellmeister, none other than Bach’s son C.P.E.) to solve its contrapuntal mysteries. Perhaps this quote should be applied to all Bach’s work. Consider the case of the Bach chest…

A true highlight of the museum—the recently discovered Bach chest with an 11 bolt locking system.

The Bach chest is the only piece of furniture now confirmed as having belonged to J. S. It has a complex locking mechanism with 11 bolts and was probably used to store valuables. The discovery of the chest as Bach’s was quite recent—just 2009. The chest had been used as a collection box for donations in the museum for a catholic cathedral in Meissen some 50 miles from Leipzig. So what tipped off a visitor that this box was J.S. Bach’s?

Only one person could have created this crest!

The answer: the crest insignia inside. It is Bach’s insignia and only Bach’s. How do we know? It simply looks like a complex abstract design.

But on closer observation, we see the initials JSB, the letters highly stylized.

My crude imitation of JSB stylized.

JSB stylized, slanted, and entwined. The reason Bach did this becomes clear later.

The next thing we might notice is that the left of the design is a ‘B’ in mirror image.

Entwined 'B's—symmetrical. When combined with the other letters entwined...

...the result is a complex diagram that looks the same and reads 'JSB' right side up and upside down. Bach would have understood Max C. Escher's artworks instantly.

The reason for the complex stylization now becomes clear. It's designed so that “JSB” appears the same whether we view the crest right side up or upside down—the letters work in retrograde inversion! Bach has manipulated the letters the same way he artfully constructs a fugue subject so that it can be combined with its backward mirror form. Unquestionably, J.S. thought in codes all the time.

The famous Hausmann portrait of J.S. Bach. What is he holding?

Take the famous Hausmann portrait of Bach—housed in this very museum— in which Bach holds in his hand a clearly marked puzzle canon in six voices (3 voices are written and the other 3 to be ‘solved’).

...He is holding a code book for a canon in 6 voices; three are provided and the other three are to be solved.

The crest with its retrograde inversion initials proved that the chest was Bach’s, and it’s apparently the only piece of Bach’s furniture of which we can be sure. And I believe understanding that Bach’s obsession with codes extended even to marking his property makes an even stronger case for Bradley Lehman’s assertion that the doodle on the cover page of the Well Tempered Clavier coded Bach’s preferred tuning method. (Read my blog “Bach’s Incredible Google-Doodle”)

The Cantata Cycle Mystery

So I did not discover a page of a missing Bach cantata while in Leipzig. Drat. But from my visit to the Bach Museum, I gather scholars are trying to find those pages themselves. In the small town of Ronnenberg, researchers determined that a student of one of Bach’s students (Tobias Krebs) had a library collection (now lost) of 51 J.S. Bach cantatas—the largest collection of Bach manuscripts outside Leipzig.

While Haydn and Beethoven both regarded Handel supreme, they had little or no knowledge of Bach’s vocal music. They did not know the St. Matthew Passion, the B Minor Mass, and the cantatas. Surely their assessment of Bach would have changed had they known this music. After all, Mozart spent just a few days studying Bach and his music was never the same afterwards! C.P.E. Bach stated that his father had written five full year cycles of cantatas for all the Sundays and feast days. So how many Bach masterpiece cantatas are missing? 25? 50? 100? 250? The first two full years of Sunday cantatas in 1723 and 1724 survive intact. Just that pace of composition alone is remarkable. The Bach-Archiv claims as its greatest treasure the 44 original part sets for Bach’s second cantata cycle (1724-1725). The third cantata cycle beginning 1725 also survives, though incomplete. If C.P.E. Bach was accurate, then the world is still missing a great number of his father’s cantatas.

You can read more about the cantatas in this superb online guide:

The Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach: A Listener and Student Guide by Julian Mincham

Did you too grow up reading stories about Bach cantatas being used as wrapping paper in the fish market after his death? That myth of ultimate composer neglect always stirred me deeply. Surely it's a myth! Or is it? How does one explain so much missing music? It’s interesting that the Bach Museum makes no mention of the deteriorating relationship Bach had with the Leipzig authorities, especially in his later years, a point his biographies make emphatic. Leipzig was searching for a new cantor well before Bach died. And after his death, Bach’s music attracted scant interest. We know C.P.E. Bach had The Art of the Fugue engraved on copper plates, yet later sold the plates as scrap for lack of buyers. Some of Bach’s music could have been discarded from disinterest, as in the famous case of the Brandenburg Concertos, not performed until a hundred years after Bach’s death.

Some scholars insist that there is no missing music, that Bach adapted previous works for the last two years of Sunday cycles, or that C.P.E. was thinking of earlier cantatas before Leipzig as part of this collection. At the current pace of discovery in Bach scholarship, perhaps we’ll have an answer to that soon.

The mystery of the missing cantatas remains open, and it inspires us to contemplate the larger preposterous but actual ethos: but for a sliver-of-a-chain of music lovers and composers extending from C.P.E. Bach from 1750 to Felix Mendelssohn in 1829—who insisted to a skeptical public that Johann Sebastian’s music was important—we would not have this Bach’s music in our world today.

The Grand Musical Conversation

So if you haven't already, I highly recommend you take your own odyssey to composer residences. In this trip, I visited eight of them— Haydn’s in Eisenstadt, Mozart’s in Vienna and Prague, Beethoven’s in Heiligenstadt, Dvorak’s in Prague (actually a museum, not a home), Wagner’s in Zürich and Lucerne, and Mendessohn’s, Schumann’s, and Bach’s in Leipzig. These visits absolutely brought me closer to their music and their lives. The style of their manuscripts, the setup of their studies, their choice of home decor and furniture, their correspondence, their business papers, and the friends that visited all come together to make them feel contemporary to us with our own lives and concerns. They had many of the same distractions, bills, and crises we all experience. They also liked to take breaks, enjoy time in nature, sought good company, looked to other people for inspiration, and spent a lot of time alone.

What comes across as extraordinary with all of them, though, is their burning intensity, not just for music, but everything. Mendelssohn’s creativity pours out of him into painting, sketching, and social change as well as composition, performance, and conducting. Haydn’s humor and interest in personal motivation has him framing his short vocal settings of various homilies on his wall. Bach isn’t content to place all his contrapuntal codes in his music, it must extend even to the way he personally marks his property. All these composers expressed their characters and what they cared about so beautifully in all sorts of media.

Above all, their music manuscripts, despite having different styles, uniformly show an extraordinary degree of detail and care. They show keen awareness of the tradition they draw from and continue/elaborate/extend in their own style. It is as if the composers through their scores are speaking to each other and forward to us in our precise time with their writing. By viewing and hearing these scores, we have the breathtaking experience of hearing a grand musical conversation about the human experience that extends through the ages.

This was thrilling to see—a beautifully engraved copy of the great St. Anne Prelude and Fugue for Organ in E flat major by J.S. Bach (one of the few pieces published in Bach's time). I know of no music more powerful. The Prelude and Fugue are bookend pieces for Bach's Clavier-Übung III, essentially his summation of the organ.

********************************************************