Entropy and Genesis—The First Movement of Beethoven’s Eroica

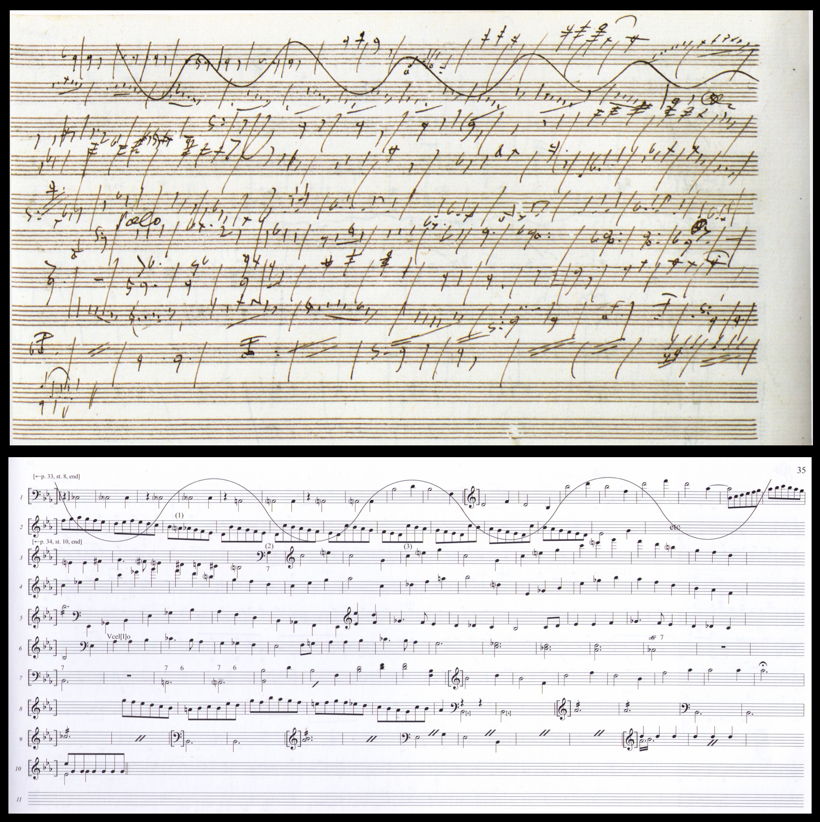

A page from Beethoven’s sketchbook for the development of the first movement of the Eroica symphony

Beethoven’s musical revolution with the Eroica symphony begins immediately with its opening two dramatic chords. Like guillotine strokes, they initiate a continual process of disruption and disintegration.

In a sense, this first movement is music in search of a theme. Every time a tune seems to begin, it crumbles away. Right after the two “guillotine strokes,” the cellos play the first 9 notes of a tune, then slip down to the “infamous” C sharp, a note foreign to the key. That “throws off” the violins, who stutter in syncopation, throwing the rhythm into question just seven bars into the symphony.

This small chaos sets off a cascade that disrupts the entire movement. The second theme? It doesn’t even try to begin as a melody, but rather just soft luminous pulsing chords in the woodwinds, either a contrast or beautiful resonance from the violent “guillotine chords” of the opening.

Even more striking, Beethoven pursues his earlier idea to confuse the meter by increasingly placing accents on the second beat of each measure, the beat that is normally the weakest. The second beat now starts to sound like the strong first beat. Near the end of the exposition, violent chords can’t decide on any meter at all—they enter on beat 1, then beat 3, then beat 2, etc. In this way, Beethoven literally destroys musical meter.

So rather than building music with themes, Beethoven focuses on a more granular level, creating five molecular “characters” that interact and evolve. We’ve mentioned three already: the “guillotine chords,” the repeated notes that stutter in rhythmic syncopation, and the “horn call” arpeggio that the cellos play at the beginning that gets cut off before it can become a full tune. The last two “characters” I call the “three note toss” and the “gallop.” The “three note toss” motive is revolutionary in its own right.* Three notes get tossed from the oboe to the bassoon, the bassoon to the flute, and the flute to the violins. With such a brief musical motive, we focus less on the notes and more on the color of each instrument. In other words, the color of the orchestra becomes an idea in itself. This provided inspiration for the vast colors that Berlioz, Wagner, Debussy, and Ravel would later reveal in the orchestra.

The “gallop” is a quick short-short-long motive that provides an electric energy to the musical texture.

These five “characters” set the stage for the longest development section Beethoven ever composed. The climax is nothing less than a musical collapse of the universe, time and space becoming a single point. The trumpets and winds overlap with the strings fusing together two different harmonies.

Those unforgettable dissonant shrieking chords are an explosion that creates a musical black hole, from which emerges a new alien world. Far, far away from the E flat major tonic we find ourselves in E minor and lo and behold, in this alien world we hear for the first time, a complete melody. But it is not completing any tune we heard partially before. It is a brand new creation.

The universe now begins to reconstruct. Harmony travels from one alien world to another, eventually finding the dominant harmony that can establish the return of the home key (E flat major) and prepare the recapitulation. But Beethoven has one more master stroke up his sleeve. The actual return is a sublime resonance of the shattering shrieking chords. Tremolo strings alternate like a whisper with the winds. They settle on the dominant harmony. But before they can resolve, the French horn enters with its E flat horn call right on top of them. During a rehearsal for the premiere, a friend of Beethoven’s criticized the horn player for being so stupid to enter two bars too early. Beethoven reportedly shot the friend a withering look.

This quiet “early” entrance is the counterforce to the destructive shrieking chords that “destroyed” the universe. The distant French horn has become the harbinger for a new genesis. A strong dominant-tonic cadence immediately follows the horn, setting the harmony to “rights” and marking the recapitulation. The issues of disruption and disintegration are recalled and expanded. Finally in the coda, we hear what we were waiting for the whole time. The horn call becomes a full-embodied, joyous theme. It is like giving water to listeners dying of thirst. Beethoven offers this theme four times in a row, going from the French horn to the violins, from the low strings to the trumpets and winds. We become drunk in triumph and victory as the music propels us to a satisfying conclusion.

But…that is only the first movement. The triumph is literally short-lived, because the next movement is a funeral. A funeral that takes these ideas of the first movement to musically depict the disintegration to life itself.

___________________________________________

*discerning ears will connect the three note motive with the moment the cello tune disintegrates, sliding down by half steps from E flat to D to C#. It’s as if this rupture slices those three notes into space where as a melodic fragment, they get tossed from instrument to instrument, searching for a complete theme.